In the world of banking wherein financial transactions take place in a large number, keeping activities safe from fraud becomes crucial. However, a question arises as to how do lenders know when a loan is fraudulent? Let’s take a look at this perspective.

Loan fraud is considered a practice wherein one person tricks a bank into giving them money dishonestly. It happens in all kinds of loans, like home loans, personal loans, or credit cards. The process of tricking the banks may involve lying about financial conditions, using fake IDs, or forging documents.

Due to the nature of their services, banks might face difficulties in accessing every loan account to find out which is a fraud one. However, there are some cues that must alert a lender:

False Information: If the person who has secured the loan has lied about their financial situation, which includes over assessing or under accessing their income, it could be fraud. Hence, banks must undertake rigorous due diligence.

Identity Theft: When a loan is secured using someone else’s id rather than personal id,this must raise concern about the authenticity of the transaction.

Fake Documents: Forged documents or lack of essential documents is a sign of concern.

Strange Activity: A person who has secured a loan or in the process of securing a loan and who has been parallelly engaged in applying for a lot of different loans all at once or who is known to change the terms of a loan very frequently could be suspicious.

The above activities can be an indication which can help banks can to filter out such kinds of transactions from normal ones. Once they know these accounts require extra attention, they need to do the following:

Documentation and Evidence: Lenders should keep a record of all important details like important documents and the transactions undertaken by these accounts and gather proof if they suspect fraud.

Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Lenders must follow all the applicable laws without any excuse. They are required to promptly report fraud to the authorities and submit all required documents which are relevant for the investigation.

Risk Assessment: It is the responsibility of these institutions to follow various risk assessment approaches for risk mitigation and securing their economic health. It includes initiating fraud prevention measures, suspending or terminating fraud loan accounts, and providing loans only after a complete background check of the customer.

Customer Due Diligence: In order to mitigate the risk of loan frauds, the economic institutions mustimplement robust customer due diligence processes that can help them identify and prevent loan fraud at an early stage. This involves verifying the identity of borrowers, document verification and monitoring account activity for suspicious behavior.

In order to have uniformity in reporting, frauds have been classified by RBI in its Master Directions on Frauds, based mainly on the provisions of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (erstwhile Indian Penal Code):

The initial decision to classify any standard or Non Performing Asset account as Red Flagged Account (‘RFA’) or Fraud lies with the bank in which the fraud account exists. It is the responsibility of the bank to report the RFA or Fraud status of the account on the Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) platform so that other banks are alerted. In case it is decided at the individual bank level to classify the account as fraud straightaway at this stage itself, the bank then has to report the fraud to RBI within 21 days of detection and also report the case to CBI/Police, as is being done hitherto.

Recently in a case which came up for hearing in the Supreme Court challenging the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) 2016 directions on ‘Frauds Classification and Reporting by Commercial Banks and Select Financial Institutions’, the bench was faced with the question wherein the borrowers were not given a chance to defend themselves before their accounts were labeled as fraudulent. The bench held that while a hearing is not necessary prior to filing an FIR, it is important to read principles of natural justice into the ‘Master Directions on Frauds’ to prevent any arbitrary actions.

The court stated that when an account is classified as fraud, it results in multiple consequences for the borrower. Initially they have to face criminal and civil proceedings when the incident is reported to investigating agencies and also it might happen that this will result in blacklisting and designating the borrower as unworthy of credit by banks.

"When a borrower's account is classified as fraudulent under the Master Directions on Frauds, it essentially results in a freeze on their credit. This means they are prohibited from obtaining financing from financial and capital markets. The inability to raise funds could be devastating for the borrower, potentially leading to severe consequences such as financial ruin and loss of rights protected under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. Debarment prevents a person or entity from exercising their rights and privileges, so it is crucial that the principles of natural justice are followed. The individual facing debarment should have the opportunity to present their case and be heard before any action is taken."

As far as the right of borrowers of being heard is concerned, the Court ruled that the principle of audi alteram partem, meaning "hear the other side", cannot be overlooked in the Master Directions on Frauds. Hence, the lender banks have to give borrowers a chance to defend themselves before labeling their account as fraudulent. It is true that the Master Directions on Frauds do not specifically prescribe for the borrowers to have a chance to defend themselves before their accounts are labeled as fraudulent but the court said that the principle of audi alteram partem must be applied to ensure that the borrowers are not unfairly treated.

Identifying a loan fraud is very important in the banking industry to uphold trust and safety placed in the lending activity and ensuring the good health of the economy. By identifying the indicators like inaccurate information, fake identities, or unusual behavior, lenders can act quickly to safeguard themselves. Establishing proper procedure is key in addressing potential fraud instances, guaranteeing that borrowers are given a chance to advocate for themselves and uphold their entitlements. Since many matter are prone to become adversarial, it is important for the lender to choose the right long-term legal partner to efficiently defend their claims.

In December 2021, a paper published by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) and JMK Research stated that despite having numerous benefits, certain new restrictions have been imposed on the banking of power of renewable energy (“RE”) which is expected to inhibit the growth of the rooftop and open-access solar market, and potentially slow progress towards India’s national target of 450 GW of installed renewable capacity by 2030.

Banking of power is a system in which a generating plant supplies power to the grid, without planning to sell it. Instead, the plant holds the option to draw back the power from the grid within a certain time and against the charges specified under relevant regulations. This concept was first introduced in Tamil Nadu in 1986 and its working is akin to a customer savings bank account.

Despite the above-mentioned benefits, over the last couple of years, governments are issuing restrictive banking notifications for renewable energy projects. Due to this, discoms are limiting their banking provisions considering the looming danger of losing high-ticket commercial and industrial clients to alternative RE power procurement models.

The Ministry of Power issued the Electricity (Promoting Renewable Energy through Green Energy Open Access) Rules which came into force in June 2022. The said rules allowed banking on a monthly basis only for open-access consumers. Moreover, the quantum of banked energy by the said consumers shall not exceed 10% of the total annual consumption of electricity from the distribution licensee by the consumers.

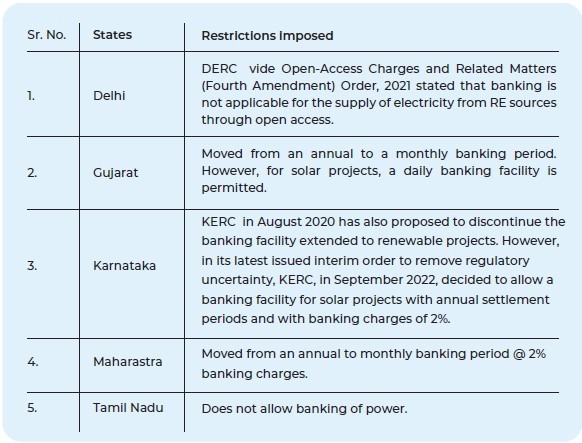

Certain RE-rich states (such as those included in the following table) have reduced the banking period from a year to a month, while others have completely withdrawn banking facilities for RE.

The rule-makers and discoms justify the new restrictions on the following grounds:

Although the points raised by discoms are valid, the national target of 450 GW GW of installed renewable capacity by 2030 seems far-fetched as it requires about INR 1.5 to 2 lakh crore annual investment whereas the actual investment in the renewable sector is estimated to be at a mere INR 75,000 crore.

Considering the gap in demand and supply, a committee of the Indian Parliament suggested the Federal Government consider imposing a “Renewable Finance Obligation for banks and financial institutions” to ensure the inflow of the requisite investment.[3] Certain other recommendations were made under the said report, as follows:

During peak summer and windy seasons, there is a high potential for excess RE generation which can later be utilised with the use of a banking facility. However, in the absence of the same and added restrictions on monthly banking of power, excess generation continues to remain underutilised. Thus, the Indian RE sector is faced with a major setback at such an early stage of its development.

As per the observations of the standing committee, the unique realities of the RE sector must be given due consideration while formulating a framework relating to financing and investments in the sector. Currently, RE projects are at the risk of being categorised as non-performing assets since revenue generation from RE is not uniform throughout the year considering its seasonality & intermittency.

Now, the RBI must consider lifting the INR 30 crore limit imposed on loans for RE projects since it is evidently not sufficient to fund mid and large-sized RE projects in India. An Energy Economist from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis opined that as per the International Energy Agency’s India Energy Outlook 2021, India would require USD 110 billion annually to raise RE deployment, and network expansion which is three times the current annual investment i.e., USD 40 billion.[4]

************

Disclaimer: The content of this piece published by White & Brief Advocates & Solicitors is intended for informational purposes exclusively and is not intended to be a piece of legal advice on any subject matter. By viewing and reading the information, the reader understands there is no attorney-client relationship between the reader and the publisher. The contents of this informational piece shall not be used as a substitute for professional legal advice from a licensed attorney, and readers are encouraged to consult legal counsel on any specific legal questions they may have concerning a specific situation.

[1] Delhi Electricity Regulatory Commission

[2] Karnataka Electricity Regulatory Commission

[3] Standing Committee on Energy (2021-22), Seventeenth Lok Sabha, Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Twenty First Report on Financial Constraints in Renewable Energy Sector, Available here.

[4] IEEFA: India Must Invest in Sustainable Energy Choices, Bloomberg Markets,

Recently, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs extended the deadline for furnishing final mega certificates to tax authorities from 10 years to 13 years from the date of import, for ten provisional power projects as indicated in the Policy.[1] The office memorandum bearing no. A-3/2015-IPC (Vol-III) dated April 7, 2022, was introduced by the Ministry of Power (“the Ministry”) to this effect.

The Government stipulated that during the extended period, bids for mega power plants (combination of intermittent renewable energy, storage and conventional power) will be invited in co-ordination with the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (“MNRE”) and Solar Energy Corporation of India Limited (“SECI”) who would further participate in such bids to secure Power Purchase Agreements (“PPAs”).

Before we understand the amendment, let's first discuss the evolution of this Policy and its importance.

Market Position and Consumer Demand

The Indian public sector lacked adequate resources to match the incremental generational requirement of additional coal mining. To plug this gap, the Ministry is exploring the possibility of setting up mega power projects with the help of private sector players thereby attracting domestic and foreign private investment from eager investors.

Another pertinent issue faced by the Indian Government in the power sector relates to its geography. While the authorities identified locations in eastern, central and coastal India endowed with naturally occurring coal and hydel power capacity, the highest demand for power in southern India. The geographical demand-supply conundrum faced by authorities demands the establishment of mega power projects to tackle the increasing demand for power on the most viable route.

When the private power policy was initiated during 1991-92, the Ministry envisaged that to improve the power supply, it would require setting up more than 10,000 MW of capacity every year in the next few years. Moreover, the fuel for such thermal power plants i.e., coal is located mainly in eastern and central India, whereas the hydel power potential is concentrated in the northeast and north but a higher demand for power is in the south and the west. It is, therefore, obvious that unless mega power projects are set up in the region having coal and hydel potential, it would be difficult to tackle the increasing demand for power on the most viable route. Establishing mega projects in the coastal regions based on imported coal also poses a feasible option.

Regulatory Changes in the Energy Sector

Pertinently, during the launch of the private power policy in 1992, the Ministry found that India requires to set up more than 10,000 megawatts of capacity each year to improve power supply in the coming years.

The public sector front lacked resources for putting up the required additional coal mining capacity to match the incremental generation requirement. Therefore, the Ministry has been exploring the possibility of setting up mega power projects through the private sector route to attract domestic and foreign private investment and the response so far has been positive.

At this juncture, it is important to note that the government amended the Mega Power Policy in 2009 to smoothen the application process to attain final mega certificates.[2]

The said modifications endow benefit of the Policy to the power projects of the following capacity:

| Thermal Power Plants | with a capacity of 1000 MW or more | or 700 MW if the plant is located in Jammu & Kashmir, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. |

| Hydel Power Plants | with a capacity of 500 MW or more | or 350 MW if the plant is in the states of J&K, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura |

B. Widening the scope of the Policy

i. The benefits enjoyed by stakeholders under the said Policy are extended to brownfield expansion projects.

ii. The benefits are to be extended to brownfield expansion projects too.

C. Interstate sale of power for achieving mega power project status has been removed.

D. The mega power projects would have to tie up power supply with power distribution companies/utilities through long-term PPA in accordance with the National Electricity Policy 2005 & Tariff Policy 2006.

E. ICB for procurement of equipment for mega projects are not required if the requisite quantum of power has been tied up or the project has been awarded through tariff-based competitive bidding.

F. The present exemption of 15% price preference available to domestic bidders in cost-plus projects of PSU would continue. However, the price preference would not apply to tariff-based competitively bid projects of PSU.

Extension of Deadline to Apply for Mega Power Project Certification

Prior to the recent amendment, the Policy only allowed a period of 120 months or 10 years from the date of import for businesses to apply for and furnish final mega certificates to the tax authorities as against the provisional mega projects. Now, the Cabinet has officially extended the said deadline by 3 years for ten partly / wholly commissioned provisional mega power plants.

Reproduced hereinbelow is the list of 10 (ten) provisional mega power projects to which the aforesaid amendment is applicable and which have been commissioned/partly commissioned so far:

| Sr. No. | Name of the Project | Project Capacity (MW) |

| 1. | Baradhara Thermal Power Plant (“TPP”) (2X600 MW), Janjgir-Champa, Chhattisgarh | 1200 |

| 2. | Anuppur TPP (2X600 MW), M.P. | 1200 |

| 3. | Uchpinde TPP (4x360 MW), Janjgir-Champa, Chhattisgarh | 1440 |

| 4. | Cuddalore TPP (2x600 MW), Tamil Nadu | 1200 |

| 5. | Lalitpur TPP (3x660 MW), Uttar Pradesh | 1980 |

| 6. | Vishakhapatnam TPP (2x520 MW) Andhra Pradesh | 1040 |

| 7. | Nellore TPP (2x660 MW), Andhra Pradesh | 1320 |

| 8. | Raikheda TPP (2x685MW), Raipur, Chhattisgarh | 1370 |

| 9. | Binj Kote TPP (4x300 MW), Raigarh, Chhattisgarh | 1200 |

| 10. | Janjgir-Champa, Akaltara TPP: U-2&5 (2x600MW), Chhattisgarh | 1200 |

Key Takeaways

The extension of time granted to businesses for furnishing final mega certificate is a thoughtful action welcomed by the concerned industry players. The extension thus granted will enable developers to competitively bid for further Power Purchase Agreements and enjoy the applicable tax exemptions under the Policy. The increased liquidity at the behest of the developers will boost the power sector’s growth in India and revive the stressed power assets.

The government will also invite bids for firm power (a combination of intermittent renewable energy, storage, and conventional power) during this extended period in coordination with the MNRE and Solar Energy Corporation of India Limited. Moreover, the ten notified mega projects will be expected to participate in firm power bids to secure PPAs.

**********

[1] Clause- I of Para- I of Amendment to Mega Power Policy, 2009 (“the Policy”) for Provisional Mega Power Projects dated April 12, 2017.

[2] Ministry of Power vide notification dated 14th December 2009

Recently, as a massive move, the Inter-Ministerial Committee (“IMC”) of the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (Highways Section) of the Government of India (“the Ministry”) in its meeting held on April 1, 2022, concurred with the proposal permitting a change of ownership from 2 (two) years to 1 (one) year after the commercial operation date (“COD”).

Subsequently, a circular bearing no. NH- 24028/14/2014-H (Vol Il) (E-134863) (“the Circular”) dated May 23, 2022, regarding the change in ownership clauses in the Model Concession Agreement (“the Agreement or MCA”) of BOT (Toll) projects was introduced.

Before getting into the peculiarities of the circular, let us get a brief idea of what is BOT (Toll) Project.

The National Highway Authority of India (“NHAI”) has adopted primarily 4 (four) types of national highway projects in the public-private partnership model, as follows:

| Sr. No. | Type of highway models | Brief Explanation |

| 1. | BOT (Toll) | This model is a public-private partnership in which the private developers/operators, invest in toll-able highway projects and are entitled to collect and retain toll revenue for the tenure of the project concession period. The private developer/operator, who eventually becomes a concessionaire, is responsible for the design, development, operation, and maintenance (O&M) of the project for the entire concession period after it is developed and put to commercial use. On the expiry of the concession period, the facility is transferred to the authority (NHAI). |

| 2. | BOT (Annuity) | In this model, responsibility for the design, development, and O&M of the road project for the entire concession period is vested with the concessionaire for the Project. But, unlike the BOT (Toll) projects, the revenue of the Concessionaire is generated through annuity payments by NHAI during the concession period. |

| 3. | Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM) | In this model, 40% of the project cost is paid by the government or as construction support or grant to the private developer. The rest is funded by the successful bidder during the construction period. Even for these projects, the revenue of the Concessionaire is generated through annuity payments by NHAI during the concession period. |

| 4. | Toll Operate Transfer (TOT) | In this model, the right of collection and appropriation of toll for selected operational national highway projects constructed through public funding are mandatorily assigned to concessionaires for a pre-determined concession period against upfront payment for a lumpsum amount to NHAI. |

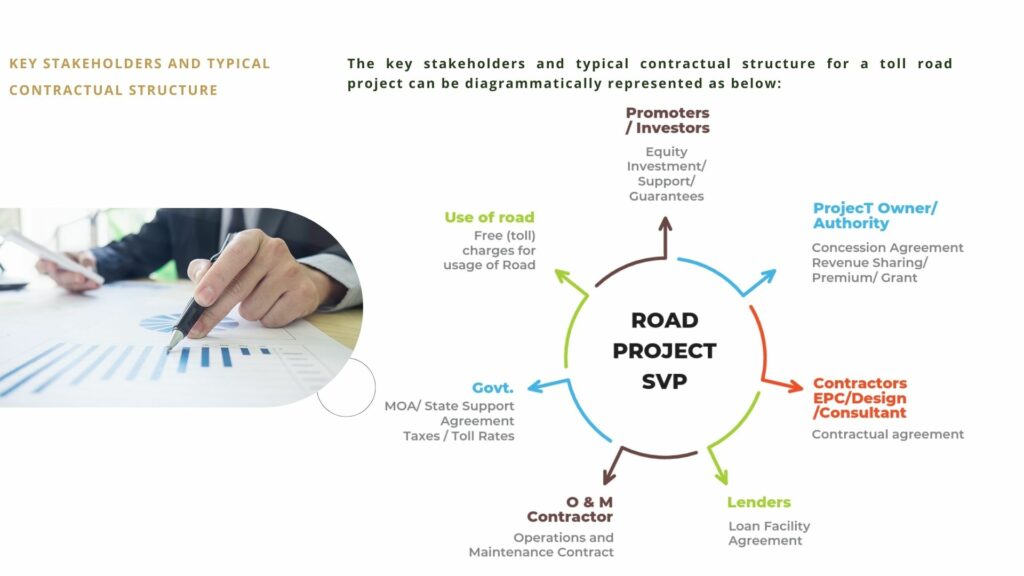

The key stakeholders and typical contractual structure for a toll road project can be diagrammatically represented as below:

FEATURES OF A BOT (TOLL) PROJECT

Original- Clause 1.1 read with Article 48 of the Agreement which defines the term “Change in Ownership” states that “a transfer of the direct and/or indirect legal or beneficial ownership of any shares, or securities convertible holding of the {Selected bidder / Consortium Members}, together with {it’s/their} Associates, in the total Equity to decline below 51% (fifty-one per cent) thereof During Construction Period and two years thereafter; provided that any material variation (as compared) to the representation made by the Concessionaire during the bidding process for the purposes of meeting the minimum conditions of eligibility or for evaluation of its application or Bid, as the case may be) in the proportion of the equity holding of {the selected bidder/any Consortium Member} to the total Equity, if it occurs prior to completion of a period two years after COD, shall constitute Change in Ownership”;

Amendment-The said Circular reduces the period of the constitution of change in ownership from 2 (two) years (as stated in the definition above) to 1 (one) year after COD.

Original- The aforesaid sub-clause states that the concessionaire shall not undertake or permit any Change in Ownership, except with the prior approval of the authority.

Amendment- The Circular amends Clause 5.3.1 to include a few conditions for the approval from the authority for undertaking Change in Ownership. The conditions are as follows:

Original- The aforesaid clause states that “the Concessionaire shall at no time undertake or permit any Change in Ownership except in accordance with the provisions of Clause 5.3 and that the {selected bidder/Consortium Members), together with {its/their} Associates, hold not less than 51% (fifty-one per cent) of its issued and paid-up Equity as on the date of this Agreement, and that no member of the Consortium whose technical and financial capacity was evaluated for the purposes of pre-qualification and short-listing in response to the Request for Qualification shall hold less than 26% (twenty-six per cent) of Equity during the Construction Period and two years thereafter; Provided further that any such request made under Clause 5.3, shall at the option of the Authority, be required to be accompanied by a suitable no objection letter from the Senior Lenders.”

Amendment- The Circular reduces the said period of 2 (two) years to 1 (one) year for holding 51% and 26% equity, respectively, during the construction period and thereafter, in the case of consortium members.

Over the last decade, the Government continued making efforts to revive the BOT model. In fact, in the current Financial Year, multiple projects under the said model would be opened for bidding.

Considering the above-discussed amendment of transferring ownership on the expiry of one year after the commercial operation date, monetization of such projects by the promoters by disposing of their stake is likely to have a positive impact on their ability to undertake more projects.

Whilst this appears to be the main objective behind the amendment, neither NHAI nor the lenders would allow any change in ownership during the construction period, since that is the most important aspect of the project, that is, the SPV, which is the successful bidder, is owned and controlled by the promoters, whose experience in the road construction and their financial status, form the basis of being qualified to take up the project. The extension beyond one year after the construction period is intended to achieve consistency and stability in the operation of the project, after the expiry of which dilution of the promoters’ stake in the SPV would not affect the project highway, its operation and maintenance and generation of revenue from the project, and thus, such dilution is not likely to hamper the interests of NHAI or the lenders.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this newsletter does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available herein are for general information purposes only.

[1] Article 5 deals with Obligations of the Concessionaire.

[2] Punch List shall mean document prepared by the contractor that lists any work that is not complete, or not completed correctly.

[3] Article 7 deals with Representations and Warranties.

An association of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) has sought a “harmonised” regulatory framework with that of banks in response to the discussion paper issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on January 22. Among the requests made by the Finance Industry Development Council (FIDC) is that of a refinancing arrangement to reduce the dependence of small and medium NBFCs on the banking system and differential risk weights for different loan categories.

“An alternative mechanism for rating these entities may also be considered to ensure that all NBFCs do not get rated on the same parameters irrespective of size, complexity of business and the niches in which they operate. The NBFCs in the proposed BL (base layer) and ML (middle layer) suffer at present due to this rigidity of credit rating templates followed by the rating agencies,” the FIDC conveyed to the RBI in a letter dated February 12, a copy of which FE has seen.

The industry has requested the RBI to articulate a road map for NBFCs in the upper layer (NBFC-UL) to convert themselves into banks. It has sought greater flexibility on matters such as deposit acceptance, raising of funds through external commercial borrowings (ECBs) and setting up of subsidiaries overseas.

For NBFCs in the middle layer, FIDC has sought “a special focus on availability of funding”. These companies would fall primarily in the BBB to AA- category in terms of their external credit rating and they continue to face fundraising challenges, the letter said.

Umesh Revankar, MD & CEO, Shriram Transport Finance Company, told FE that among the representations made by the industry (not by the FIDC) is also a request to reduce the frequency of rotation of statutory auditors. “One of the points is that of the frequent changes required in statutory auditors every three years. We have suggested that it can be every five years,” he said.

Girish Rawat, partner, L&L Partners, explained that currently, the Companies Act, 2013, lays down that prescribed companies are required to mandatorily rotate their auditor. An individual auditor cannot serve for more than one term of five years and an audit firm cannot serve for more than two terms of five consecutive years, with a cooling off period of five years. The RBI has proposed a uniform tenure of three consecutive years for auditors of NBFCs in the middle layer and above, with a cooling off period of six years.

Some experts are of the view that the frequent change in auditors could leave gaps in the audit process. Prateek Bansal, associate partner, White & Brief Advocates and Solicitors, said that the mandatory rotation of auditors leads to increased compliances and processes within the NBFCs. “Now, the proposed time frame of rotation after every three years is further alarming as the likelihood of faulty audits increases due to the short time period allowed to an auditor to become fully acquainted with the system and operations of a company,” he said. “The proposed time limit must be increased to at least five years, which will also be in line with the provisions of Section 139 of the Companies Act, 2013.”